How come making a struct in Zig less densely packed can give a huge performance increase, with far less variability? This post takes a look at false sharing and how it can be caused by packed data layouts and unintended field reorderings.

While packing data closely together can be beneficial due to cache locality, false sharing must be taken into account when designing optimal data layouts for multithreaded programs.

False sharing occurs when the data layout is at odds with the memory access pattern, namely threads updating thread-specific data that happens to fall on the same cache line.

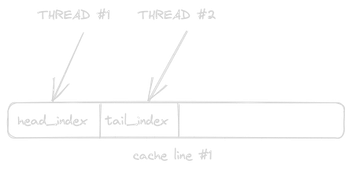

Imagine we’re writing some sort of concurrent queue where multiple threads update head- and tail indices. To avoid false sharing, we must to go from this situation:

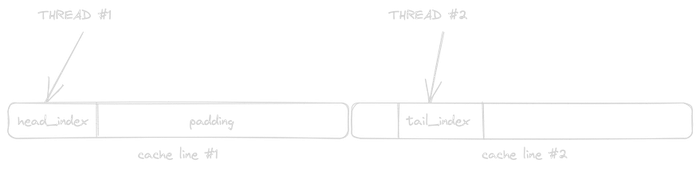

To something like this:

Thread 1 only cares about head_index, while thread 2 only cares about tail_index

By padding the struct, we ensure that each thread has its own cache line and can thus update its field without invalidating the other thread’s cache line.

A cache line is the smallest unit of transfer between each core’s local Lx cache and main memory, and thus also the unit of synchronization of coherence protocols such as MESI. Updating a cache line on one core will invalidate the corresponding line on all other cores’ local caches.

Cache line invalidation is expensive, and may additionally cause issues for applications that are sensitive to performance variability. The actual impact depends on a thread’s affinity to core socket and hyperthreads, scheduling, and the number of threads. Memory access not involving false sharing may also be affected due to intra-socket coherence traffic saturation.

A cache line is typically 64 bytes, but this varies between CPU architectures. Tools such as lstopo are useful to determine the cache hierachy and line size on your CPU.

Regular struct vs extern struct

Take a look at this Zig struct:

const Queue = struct {

head_index: u64 = 0,

padding: [64]u8 = undefined,

tail_index: u64 = 0,

};

Now imagine you have two threads updating head_index and tail_index respectively.

Changing the struct to the following makes my benchmark run 56% faster on an Intel Core i9, and with an order of magnitude lower standard deviation:

const Queue = extern struct {

head_index: u64 = 0,

padding: [64]u8 = undefined,

tail_index: u64 = 0,

};

The difference? The extern keyword. This tells the compiler to adhere to the C ABI, which means the compiler will not reorder the fields.

For regular structs, Zig is free to reorder the fields to minimize padding, which is a good thing in general.

However, by enforcing the specified order, the padding field fulfills its intended purpose: It places head_index and tail_index on separate cache lines.

The code

The benchmark is designed to demonstrate the issue at hand, and the results are not necessarily representative of false sharing slowdowns in a real-world application. That said, if false sharing occurs in a hot path, the impact can be significant.

const std = @import("std");

// Remove "extern" or the padding to observe false sharing

const Data = extern struct {

head_index: u64 align(64) = 0,

padding: [128]u8 = undefined,

tail_index: u64 = 0,

};

fn updateHeadIndex(data: anytype) anyerror!void {

for (0..2000000000) |i| {

data.head_index += 1;

std.math.doNotOptimizeAway(i);

}

}

fn updateTailIndex(data: anytype) anyerror!void {

for (0..2000000000) |i| {

data.tail_index += 1;

std.math.doNotOptimizeAway(i);

}

}

pub fn main() anyerror!void {

var data: Data = .{};

var head_thread = try std.Thread.spawn(.{}, updateHeadIndex, .{&data});

var tail_thread = try std.Thread.spawn(.{}, updateTailIndex, .{&data});

head_thread.join();

tail_thread.join();

}

The doNotOptimizeAway(i) call introduces a barrier that prevents the compiler from optimizing away the loop (which wouldn’t make for a useful benchmark)

zig build-exe -OReleaseFast falsesharing.zig

hyperfine --export-json results-with-extern.json ./falsesharing

Do the same without the extern keyword (rename the json output filename in the hyperfine command), and observe the difference.

Result

Timings are measured in seconds.

| No false sharing | False sharing | |

|---|---|---|

| mean | 3.0299017825599996 | 4.738531733004999 |

| stddev | 0.011379971724662449 | 0.13044659161376454 |

| median | 3.02725268766 | 4.7289631684049995 |

| min | 3.01537040366 | 4.582206681904999 |

| max | 3.0460710066599996 | 5.081537872905 |

The actual runs:

| No false sharing | False sharing |

|---|---|

| 3.0440456 | 4.5822066 |

| 3.0200773 | 4.7326414 |

| 3.0460710 | 5.0815378 |

| 3.0245974 | 4.6807162 |

| 3.0153704 | 4.7508973 |

| 3.0307415 | 4.7335685 |

| 3.0283079 | 4.6781897 |

| 3.0449196 | 4.7252849 |

| 3.0261973 | 4.7423249 |

| 3.0186892 | 4.6779495 |

Hyperthreading adds a twist

The timings above are with hyperthreading disabled. With hyperthreading enabled, the penalty for the false sharing case is sometimes less severe (depending on affinity), but average run times are still much worse than the no false sharing case. Hyperthreading also adds more variance, 0.06 vs 0.011 standard deviation.

On Linux, you might want to consider using pthread_setaffinity_np to pin threads to physical cores.

This is currently not supported on macOS. For the purposes of replicating this benchmark, you can disable hyperthreading by entering safe mode and entering these commands in the terminal:

nvram boot-args="cwae=2"

nvram SMTDisable=%01

After rebooting, System Information (click Apple icon in the menu bar while holding Alt) should report `Hyper-Threading Technology: Disabled"

Resetting the NVRAM will re-enable hyperthreading.